- Home

- Peter Drew

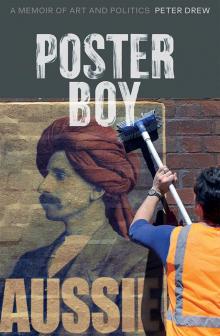

Poster Boy Page 5

Poster Boy Read online

Page 5

My dad hated it but begrudgingly indulged our obsession, buying us books about warfare and taking us to historic sites. In truth, my dad was just as fascinated by war as we were. He just hated the way us boys had zero comprehension of the horror. When I was twelve, we all visited the Normandy beaches. My brothers and I would slip into fantasy and imagine the thrill of killing the enemy and blowing stuff up. Dad knew exactly what we were up to. He’d always be waiting for his moment to bear down on us with ‘it’s not fun to have your guts ripped out’, or something along those lines.

Despite Dad’s best efforts, I brought home from France a very real-looking toy handgun, the kind you couldn’t possibly buy in Australia. The only thing that made it look like a toy was a piece of orange plastic inside the gun barrel. I devised a way to remove the offending piece of plastic using Dad’s electric drill, but before I could finish the job my gun had disappeared. I asked Dad again and again if he’d taken it but he was a stone wall of denial. I knew he was lying, but what could I do? A few months later I discovered girls and I never read another book by Tom Clancy.

Throughout my life I’ve seen the Anzac legend grow, through state funding and a culture of mandatory reverence, to become the centrepiece of Australian’s national mythology. As a boy I first learnt about Gallipoli through Peter Weir’s 1981 film. We watched it in school. Years later I had the experience of watching the film with an American audience in the States, which somehow amplified its effect. It’s an odd film, for an odd mythology. Watching it as an adult, you notice that the Turks are hardly in it. The real enemies are the British. The real enemy is imperialism. That’s even the way it was taught to us in school.

The film captures something I love about Australian identity: its untheorised dynamism. I’m impressed by the fact that an artist like Weir can make such a powerful statement on Australianness that it rivals any political speech or stately document. But every year the Anzac legend trades a piece of that dynamism for its increasingly monolithic status. There’s something cowardly about its dominance. There’s something stingy about the way it’s used to monopolise Australianness.

I have a theory that Australia’s radical left and conservative right are unwittingly united by a deep lack of faith in Australia. Both sides lack the courage to imagine a bigger, stronger Australian identity. Why not three pillars of Australian identity that offer equal reverence to Anzacs, immigrants (including settlers) and First Australians, united by the notions of courage and sacrifice? That was the point of this poster.

I only printed a handful to see if it worked. Posters need to be simple and I had some worries that this one was too complex. I had a few interesting chats while putting them up on the streets.

‘That’s not right,’ one bloke said as I finished off a poster on the back of the Exeter Hotel on Rundle Street. ‘Would you parade one of those at an Anzac Day service? It’s disrespectful to the fallen.’

I don’t like being highroaded, so I let him have it.

‘I think comparisons like this can strengthen the relevance of the Anzacs. Imagine if we had a similar level of reverence towards the First Australians as we do towards the Anzacs – it wouldn’t hurt. I’m not denigrating the Anzac legend. I’m just saying that it’s a good model for improvements to Australia’s identity. This centenary could be the high-water mark for the Anzac legend if we don’t figure out ways for courage and sacrifice to have a role in our daily lives.’

But he barely looked at me. He just stared at the poster and said, ‘Nah, it’s not right,’ then shook his head and walked away. I didn’t blame him. My poster didn’t exactly explain how we might use courage and sacrifice in our daily lives. I started to wonder whether my poster was a little too ambitious. If it didn’t work even after I stood next to it and explained it, it was safe to say I’d bitten off more than I could chew. But my favourite reaction came the following week, from an American.

I’d flown to Sydney for the ABC Lateline interview with a couple of spare days to stick up posters. I was putting up the ‘Courage and Sacrifice’ poster in Kings Cross when I heard an American accent behind me: ‘Excuse me, would you explain to me what this is all about?’

I felt immediately at ease. Americans are so polite, and this guy clearly had no skin in the game. I walked him through the poster.

‘Oh, I’ve seen Gallipoli,’ he said. ‘Why do you Aussies celebrate that? I mean, you lost!’

For a moment I thought he was joking. But he was genuinely confused. ‘There must have been battles Aussies have won,’ he went on, ‘but you celebrate the one you lost!’

He honestly couldn’t wrap his American brain around the idea that sacrifice was more meaningful to our national mythology than notions of victory. I don’t blame him; after all, Americans love to win. But most of them love Jesus too, and the Anzac legend is nothing if not a secular adaptation of Christ’s blood sacrifice. It’s even there in the final freeze frame of Weir’s film. Archy dies in agony, arms outstretched, head facing up towards the heavens, crucified.

Maybe my poster wasn’t so bad after all? There’s always going to be people who just don’t get it, so maybe I should judge it by its success rate and not just its rate of error? In any case, I had to focus on the mission at hand. The ABC wanted to speak to me about my current project so I put ‘Courage and Sacrifice’ aside for another time. The meta-jumble of Australian identity could wait.

I met Jason Om at the ABC’s Ultimo Centre in Sydney. It’s an intimidating building that triggers my deep distrust of bureaucracy. They make you wait in the central atrium, where I felt out of place in my work gear. All around me I could hear the building hum as it sucked up, digested and excreted vast amounts of information. I’d just walked into the beast’s open mouth and politely sat on its tongue. By the time this building was done with my story, I’d taste young, simple and sweet, perfect for mainstream consumption. If I failed to play that role, I’d be spat out, never to return. I was ready to play along.

Jason followed me around the streets as I stuck up posters. I posed inside Central Station and outside the Town Hall. Finally, we stopped for an interview. It went fine. We spoke about how the project had become a movement and how pleased I was that other creatives were getting involved.

Afterwards, Jason disappeared into the ABC building and I walked back to my hostel. I was beginning to feel dislocated from my own story. Someone else was telling it for me. I felt scared and a little bit sick, so I stuck up more posters until the feeling went away.

My Father’s Son

I’ve noticed over the last few years that I’ve gradually become a bit twitchy when nobody else is around. I’ll be working on something when suddenly a shameful memory will appear in my mind, causing me to twitch, grunt or swear. It probably felt good at first, like a little release valve. But sometimes I can’t control it. If I’m stressed, it’ll happen right in front of Julie. We’ll be driving somewhere and during a lull in the conversation I’ll drift into my own thoughts then suddenly wince with a short, sharp ‘Ahh!’ Julie reacts with shock and concern, but she knows to leave it. She knows when I’m not ready to talk about something. Lately it’s been getting worse, which makes me think that I need to reveal some things that I’m not proud of.

After the Lateline interview in Sydney I was back in Adelaide for less than twenty-four hours before leaving again for Western Australia. Normally Julie and I are around each other constantly, but over the course of the project I’d already been apart from her for almost a month. We’d talk over the phone every night. She’d be at home lying in bed while I’d be crouched outside my hostel dorm, alone in the corridor. I was enjoying being immersed in my work but I still needed someone to listen to my worries. It was pretty unbalanced but we were accustomed to carrying each other’s weight during creative projects. When it was market season, Julie’s work came first and I became her pit crew. In that way we fed off each other’s ambition, so I bounced in and out of Adelaide without a care.

; Since the project had blown up in the media I’d been contacted by dozens of people who wanted to help out. When I announced that I was coming to Perth I received a message from a photographer who lived in Fremantle. Her name was Sarah. She offered to drive me around Perth and document my process. I turned down most offers for help because postering is really a one-man job. But Sarah’s offer was perfect: she’d be out of the way taking photos and I needed a driver.

I’d already been postering for a few hours when Sarah picked me up. I noticed immediately that she was attractive. Not in an obvious way; she had an interesting beauty, which made it worse. My eye kept going straight to her top lip. It had this little dip in the middle that I’d never seen before. We started chatting and the connection was effortless. It felt like a betrayal from the very beginning, as if a boundary had been crossed the moment I said hi.

All day she took photos of me. A good photographer lets you enjoy the narcissism just enough to be in the moment. Sarah was a good photographer. I wanted to be a good subject so I tried to hit some risky spots by climbing abandoned buildings and leaning off the roof to poster the side walls. We stayed out all day, and in the evening some of her friends joined us. Now I really started to show off. I stuck up one poster on a rail overpass while a train went past overhead. I was terrified but acted as if it was nothing.

The next day Sarah took me out again and we continued to have a blast. It was just her and me. I stuck up posters all day and she dropped me off in Fremantle. As soon as she left I missed her. It wasn’t a concept in my head. It was a physical longing. I tried to put it out of my mind by putting up more posters. When I got back to the hostel that night I watched myself on Lateline. It’s a strange experience seeing yourself on TV. More accurately, it’s a strange jolt to your ego seeing yourself on TV. It’s fame, plain and simple, and my attention-starved ego ate it up.

When I got back to Adelaide I was still thinking of Sarah. Everything around me felt cold. I started to feel physically weak. Day after day a feeling of pain lingered. I had three days to prepare before leaving for Brisbane, and the whole time I couldn’t connect with Julie. She was as busy as always but I felt that a door had closed inside me and I was cut off. Emotionally I was completely untethered. Without anyone to speak to, the stuff in my mind was scrambling to find an exit.

I’d been happily married for five years yet I was seriously considering throwing it all away over a feeling that had bubbled up out of nowhere. It made me angry. I felt I understood the whole thing but my understanding counted for nothing. I wanted to change the way I felt but I couldn’t. I knew it was my ego gone mad but I didn’t know how to regain control. I knew it was because I’d been spending too long away from home. I barely knew Sarah. I just wanted it to stop. Maybe if I waited it would go away?

I couldn’t tell Julie. Why hurt her when my current feelings would probably just pass? So I left Adelaide for Brisbane without saying a thing. For three days I put up posters in a miserable funk. This feeling that had taken hold of me was stronger than anything I’d felt in years. Feelings mean things, right? Maybe this was the right step for me? Maybe I could just leave everything behind and live in Perth? I had to find out if Sarah felt anything for me. I sent her a message.

Hi Sarah, I’m sorry if this comes as a weird surprise but ever since we met I can’t stop thinking of you. If you could figure out a nice way of letting me know that I’ve got it all wrong that would be great.

Hi Peter. It was lovely to meet you during your time here … but this really does come as a surprise.

Yeah, sorry. I think I’ve just been spending too much time away from home … I feel better already just admitting that.

No, I didn’t. I felt like a complete piece of shit. I’d basically entrusted my marriage to the whim of another woman, who luckily didn’t feel anything for me. I was sick with relief and self-pity, so I cried it out like a child. Miraculously I’d been given a whole dorm to myself so I was free to wallow. After an hour or so I felt empty, so I shook it off and went out to stick up more posters.

I decided to just forget about what had happened. I wouldn’t tell Julie. What would be the point? Nothing had even happened, I told myself. As I walked around Brisbane I could feel the whole drama melting away into nothing. But in reality I knew that I’d properly lost control. This was a little more serious than losing my shit on the lawns of Melbourne Uni. This time I’d been ready to flip the table on my entire life.

What made it most disturbing was the fact that I’d spent years telling myself I’d never be like my dad. No matter what, I was committed to Julie, and it wasn’t a naive promise – it was a discipline. I guarded my attention strictly. My imagination never had time to play outside of my relationship with Julie, so she never had any reason to feel jealous. But despite my best intentions and clever strategies, all it took was a feature on the ABC to tip my ego over the edge, and I’d lost control.

I was sticking up a poster on Wickham Street in Fortitude Valley when an old thought crossed my mind with new force. What if there’s something universal, and fundamentally human, about my weakness? What if that weakness lies at the core of all wrongdoing? Wouldn’t that mean I’m really no better than the worst racist? Maybe we’re all filled with ancient destructive impulses, lurking deep within us? What if we all lose control from time to time but some of us get lost in our mistakes?

In that instant I knew I had to find a way to forgive my dad. The thought was a long way from becoming action, but I sensed a switch had just flipped inside me. I stayed with that feeling for as long as I could. My body was on auto-pilot as it walked the Valley, sticking up posters. Inside my head, a new feeling was shining a light on the dusty assumptions of my brain. Unfortunately the dust was pretty thick.

It’s an uncomfortable idea that there’s very little separating you from the things you oppose. It’s the sort of idea that you play with for a while, before eventually running top speed in the opposite direction. So the very next day I went in search of some real racists to make myself feel better. I shouldn’t have trouble finding some, I thought. After all, this was Queensland.

The Heart of Daftness

Along with the Northern Territory, Queensland was the other place that people couldn’t wait to warn me about … Actually, I was also warned about Tasmania. Come to think of it, the only place I definitely wasn’t warned about was Melbourne. So, allow me to warn you: Melbourne is where all the other cities dump their most annoying wankers. I’d hate Melbourne if it wasn’t filled with all my old friends from Adelaide.

In Brisbane I knew nobody. Brisbane was lonely in the best possible way. I needed some alone time. When I’m feeling disgusted with myself I tend to project my contempt outwards, at anyone within throwing distance. Luckily I could sublimate my defective personality into a wholesome activity. I was sticking up posters at a cracking pace. If anything, I needed to slow down, or perhaps find a special target for my last few dozen.

My friends had told me that Queensland was full of racists but, sadly, I’d encountered none. Instead, my social media feed was full of people getting behind my poster with big smiles of support. It didn’t sit right with my mood. Where was the conflict? I wanted to go out and find it, get right in its face, stir it up a bit, then exploit it for likes on social media. I decided to set out on a little racist safari, so I gathered up what was left of my posters and set off for Roma Street train station. I was going to visit Pauline Hanson’s old stomping ground. I was on a mission to Australia’s heart of daftness. I was going to Ipswich.

Imagine my disappointment when I discovered that Ipswich was practically within walking distance of Brisbane. I needed something more adventurous, so I bought a ticket for Toowoomba. It was further away, more rural and therefore more racist. I could visit Ipswich on the way back.

After a beautiful train ride through the lush countryside I arrived in Toowoomba to discover a town in the middle of its own street art festival. The First Coat Intl’ Art Festival

boasted an impressive, multicultural rollcall of artists and performers that threatened to shatter my fantasy of Toowoomba as a bigoted, rural backwater. But I wasn’t fooled. I was determined to find the real Toowoomba. I walked away from the murals, music and happy crowds. I walked to the quieter side of town, where I spotted the Metropole Hotel. From the outside it looked like a perfectly miserable drinking hole. I stepped inside with my posters, expecting to meet the cast of Wake in Fright. I was going to show them my posters and get a reaction. Instead I met Mohit, who had just arrived from India. Zoey the publican proudly explained that Toowoomba is Queensland’s second biggest centre for the resettlement of asylum seekers. I smiled through my disappointment.

I gave away some posters to my new friends at the Metropole before sticking up more around town. Toowoomba had turned out to be upsettingly lovely, but I still had Ipswich. I found the address of Pauline Hanson’s old fish and chip shop, Marsden’s Seafood. I could walk in there with my poster, cop some abuse and then boast about it on social media to provoke outrage. Plenty of other activists behave that way, so why shouldn’t I?

It was almost an hour’s walk from Ipswich Station to Marsden’s Seafood, so I had time to think. If I went down this path of manufacturing conflict I’d quickly join the tribe of Twitter activists who constantly bait and shame their detractors. I could harvest the abuse I attracted online and never be lacking inflammatory content. Once the trolls caught wind of the fact that I’d happily publicise their abuse, they’d come from miles around to outdo one another. I could sit back and stir the pot, an expression of concerned discomfort on my face for the cameras. Sure, everyone would know I was a feckless hack, but they wouldn’t be able to say so without appearing to oppose my righteous cause. ‘Better a hack than a bigot’ would be my fallback position.

Poster Boy

Poster Boy